Making a BLE Wireless IBM Model M

· 1454 words · 7 minutesTL;DR

Yes. It’s great and I daily drive it. I wrote this entire article with it. It’s on GitHub, both the PCB design files and firmware.A while ago, I went through one of the most important rites of passage a developer can take. I got into mechanical keyboards.

It started tame. A highly-respected online retailer was shutting down and was selling all of their branded products for cheap, so I got a clicky TKL and a silent 96%, both of which I still love using.

Then I heard about the infamous IBM Model M with its buckling spring switches. And it was perfect. A keyboard built like no other. It was the missing piece, a keyboard to surpass Metal Gear.

See, the Model M doesn’t work like the keyboards of today. IBM developed and patented their own switch mechanism - the buckling spring.

Each key is connected to a flapper through a spring, and when the key depresses to a certain point, the spring cannot hold upright and collapses (or buckles), which moves the flapper that completes an electrical connection.

This results in a key press that you can physically feel, and it sounds sooo good. And loud. Because the loudness war has ended, and loudness won.

Getting My Hands on a Legend

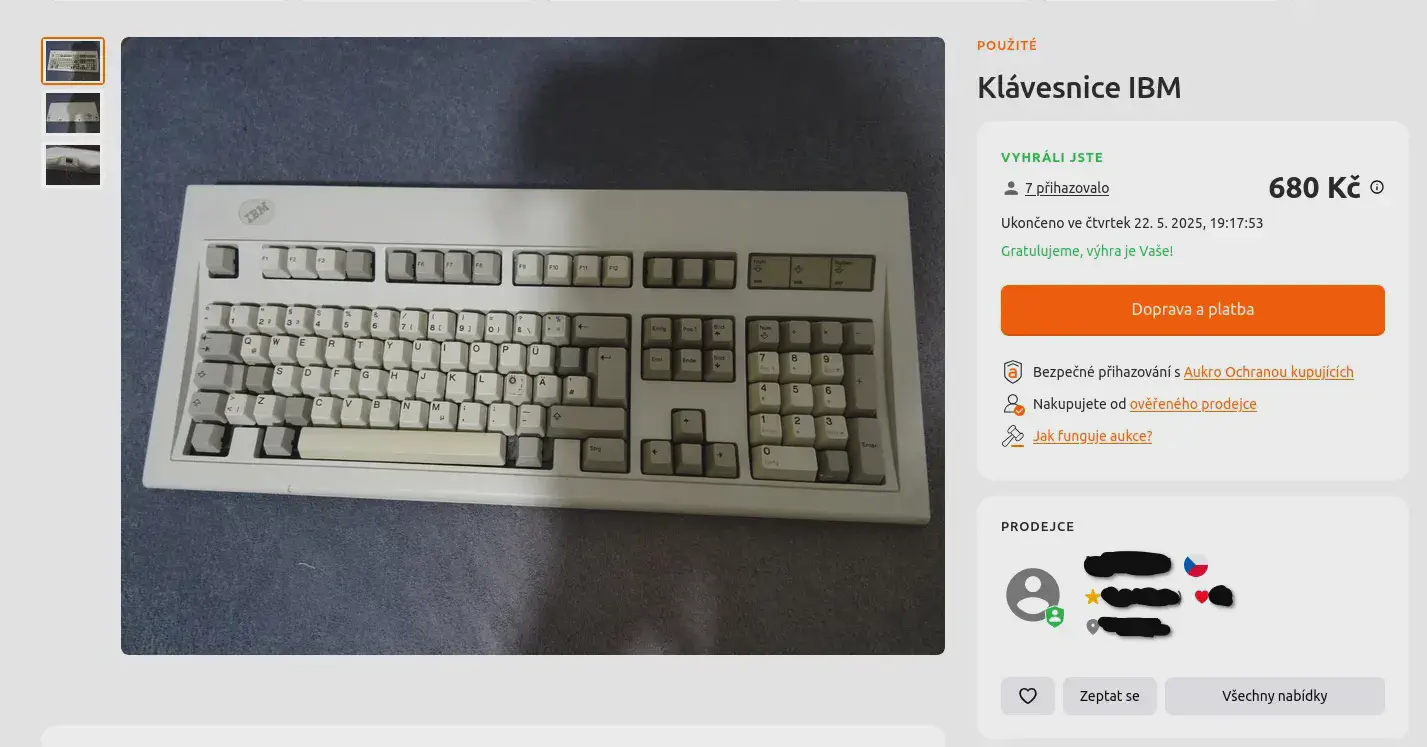

##So obviously I wanted one. After scouting websites for about a month, I got one quite cheap.

It wasn’t in the best shape, as you’ll see later, buuut it was in one piece and seemed to be mechanically functional, so I took it.

The keyboard, other than being dirty and needing a good clean, was in good condition considering its age.

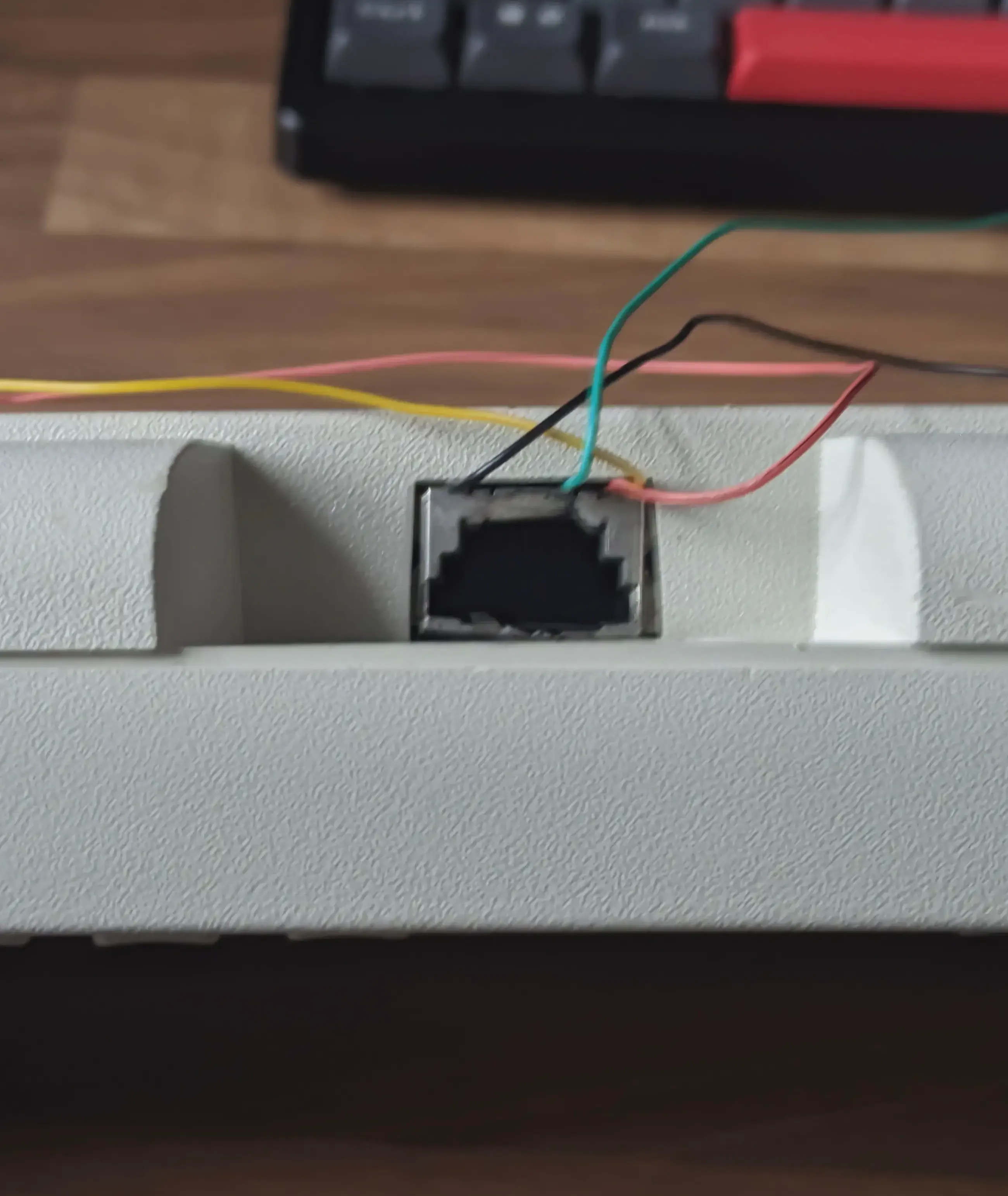

It didn’t have any serious issues. Sure, some keycaps were gone, but you can still type without them. The space bar stabilizer was gone, so pressing space was difficult1, but I managed to source one. The original connector was beyond saving and “repaired” by the previous owner(s?) with four wires coming from the bottom, but I wasn’t going to use the board anyway.

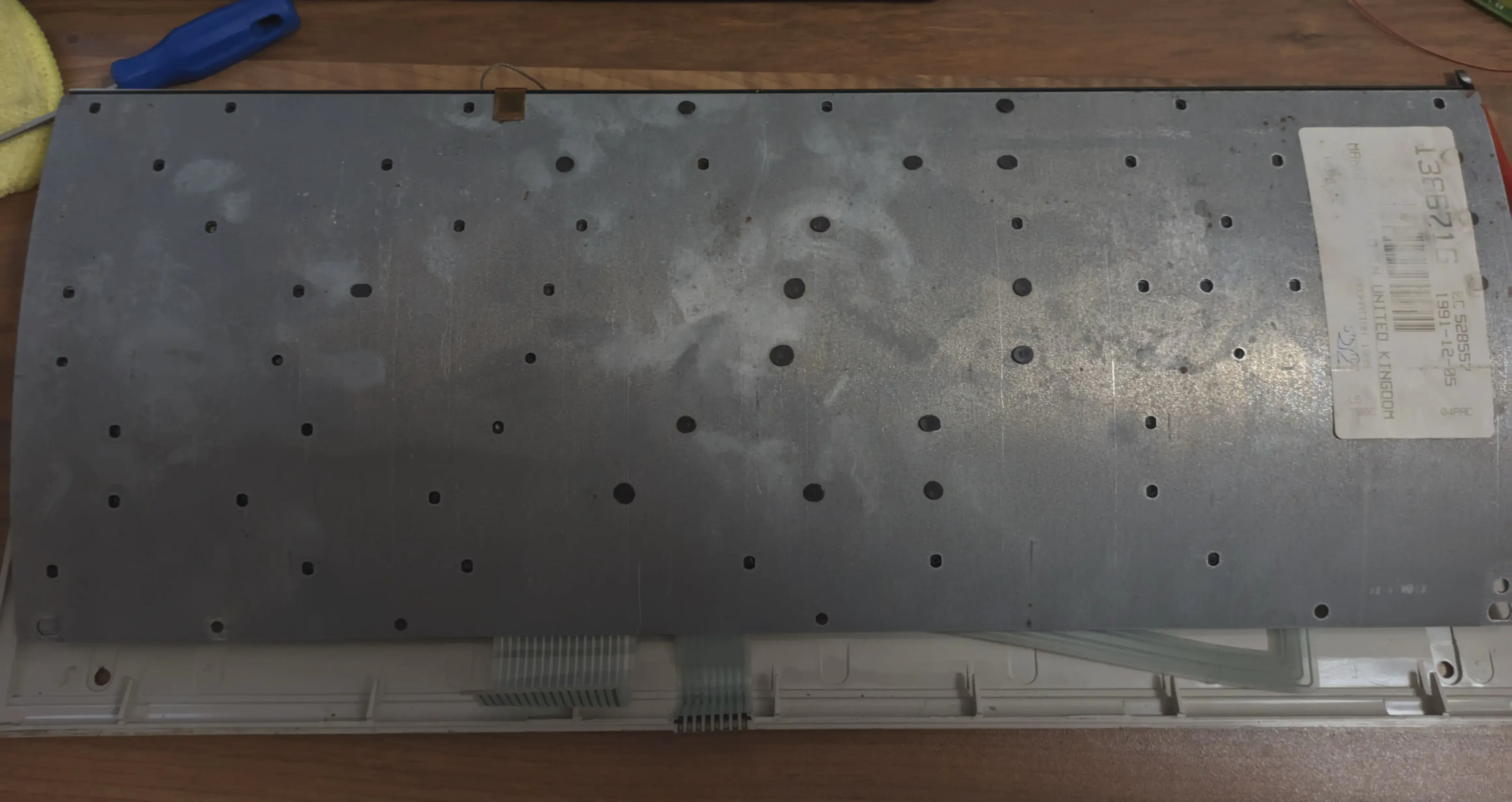

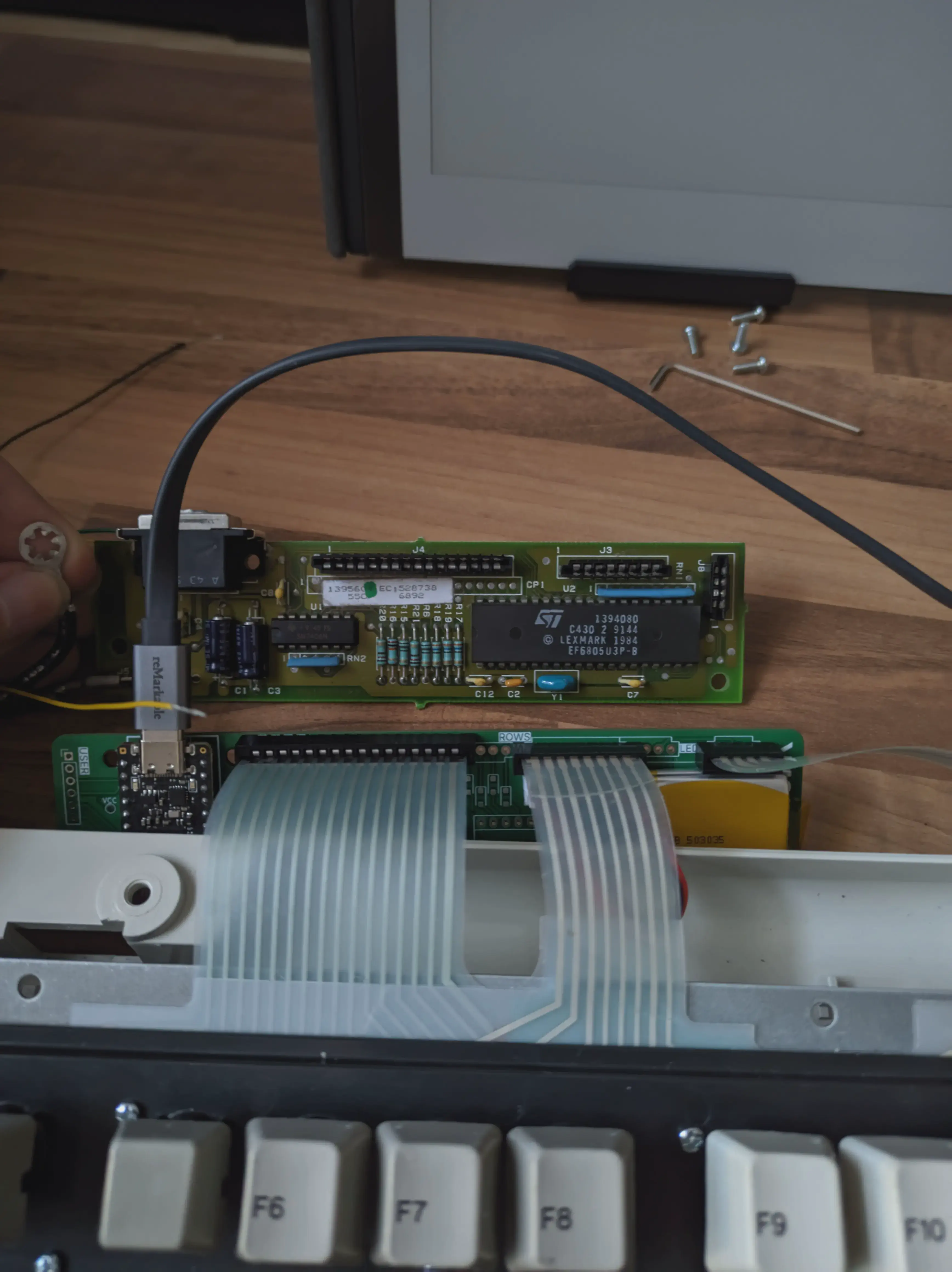

Once you remove the chassis, you are left with the controller on the bottom and the internal assembly, consisting of a front plastic baseplate, the flappers, foam, plastic membrane, and metal backplate.

The only major problem that needed urgent fixing was the plastic rivets that hold the assembly together. Due to its age, most of the rivets became brittle and broke off, making some keys not click and making the keyboard feel unstable. It’s not comfortable to type on a keyboard when with every key press you can feel the whole assembly bending.

Before even making any hardware, I took a risk, and drilled holes in the frame to replace the plastic rivets with nuts and bolts. This is quite common as the rivets do not age well at all, and it’s referred to as Bolt Modding in the community.

The Little Controller That Could

##Now that the keyboard was in a stable condition, it was time to mod the hardware.

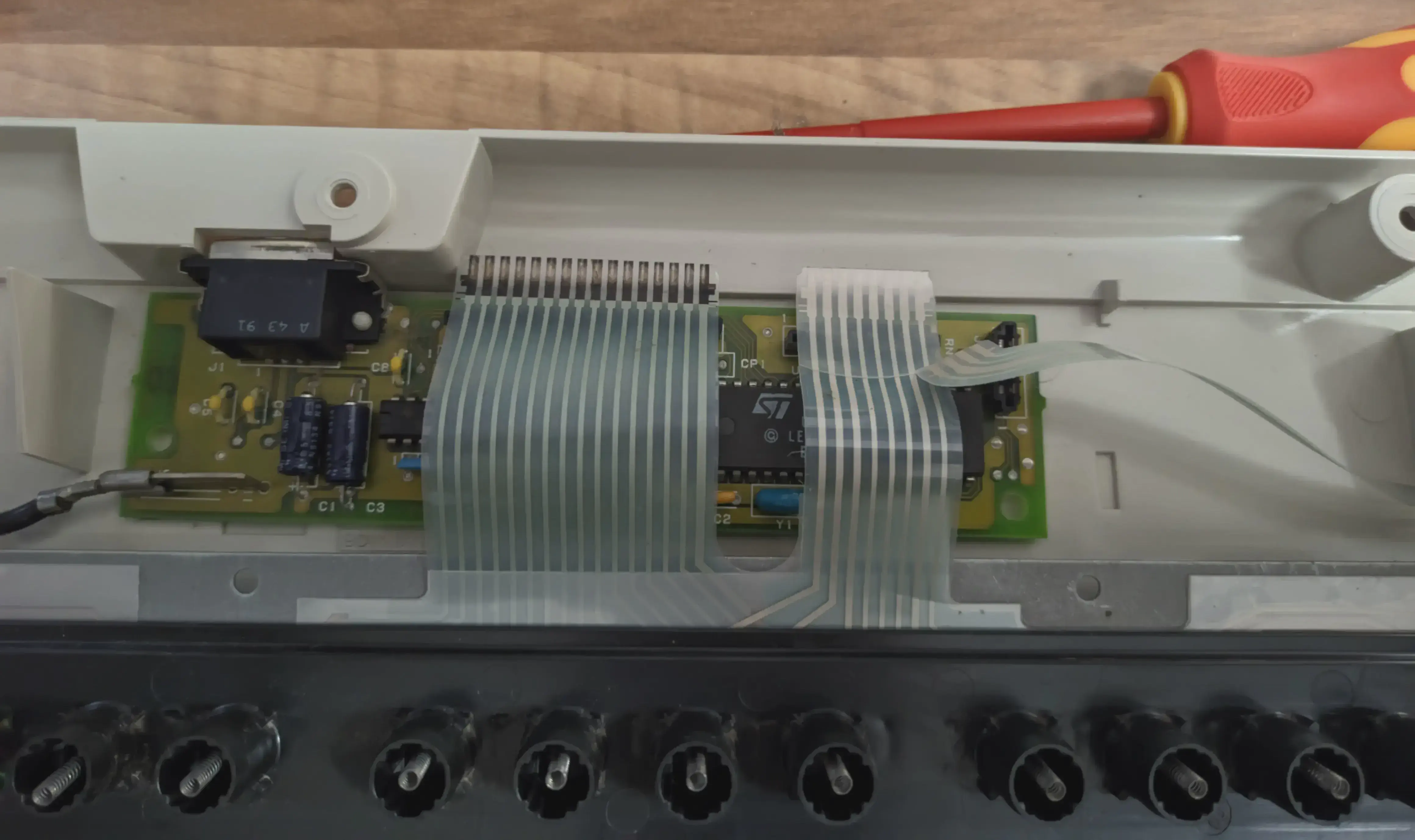

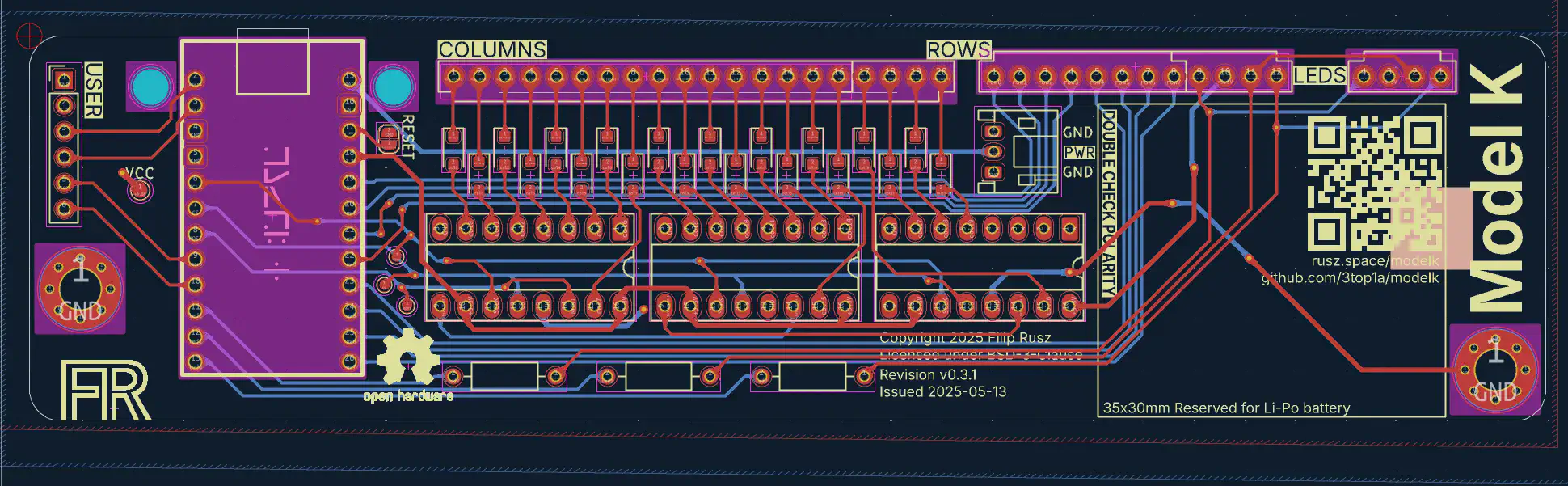

The plan was deceptively simple: Design a custom PCB, named the modelk, with a wireless microcontroller that would scan for key presses like the old one, but had USB-C and Bluetooth.

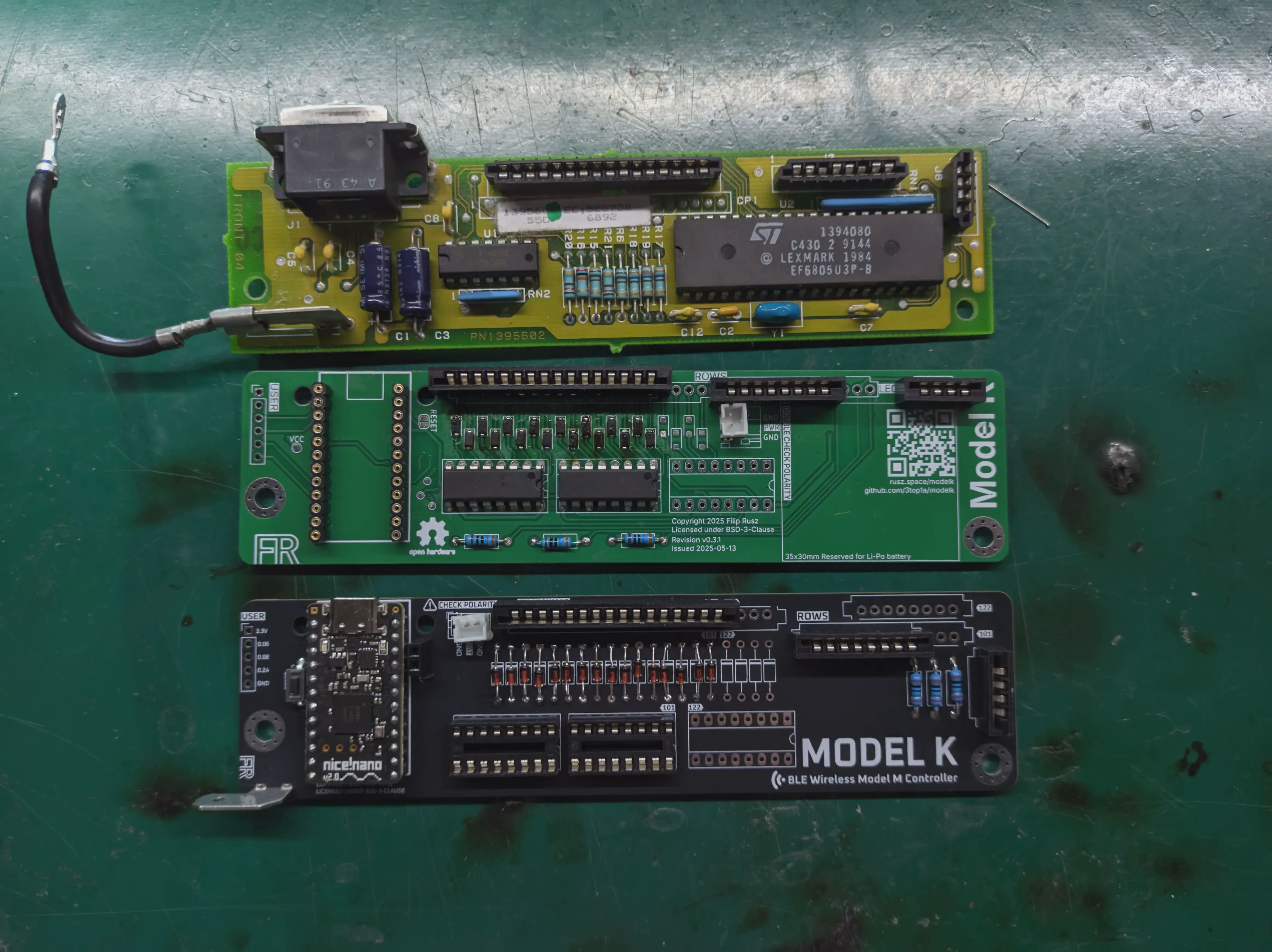

I wasn’t the first to attempt this. One of the more popular modded controllers is the wired-only Model H by John Hawthorn. As I did not have the keyboard when I started designing the board (lol), I forked the Model H on GitHub and used his design as a starting point for mine. I redid the entire schematic as my design didn’t share any part, but kept most of the PCB as I didn’t have a reference in hand yet.

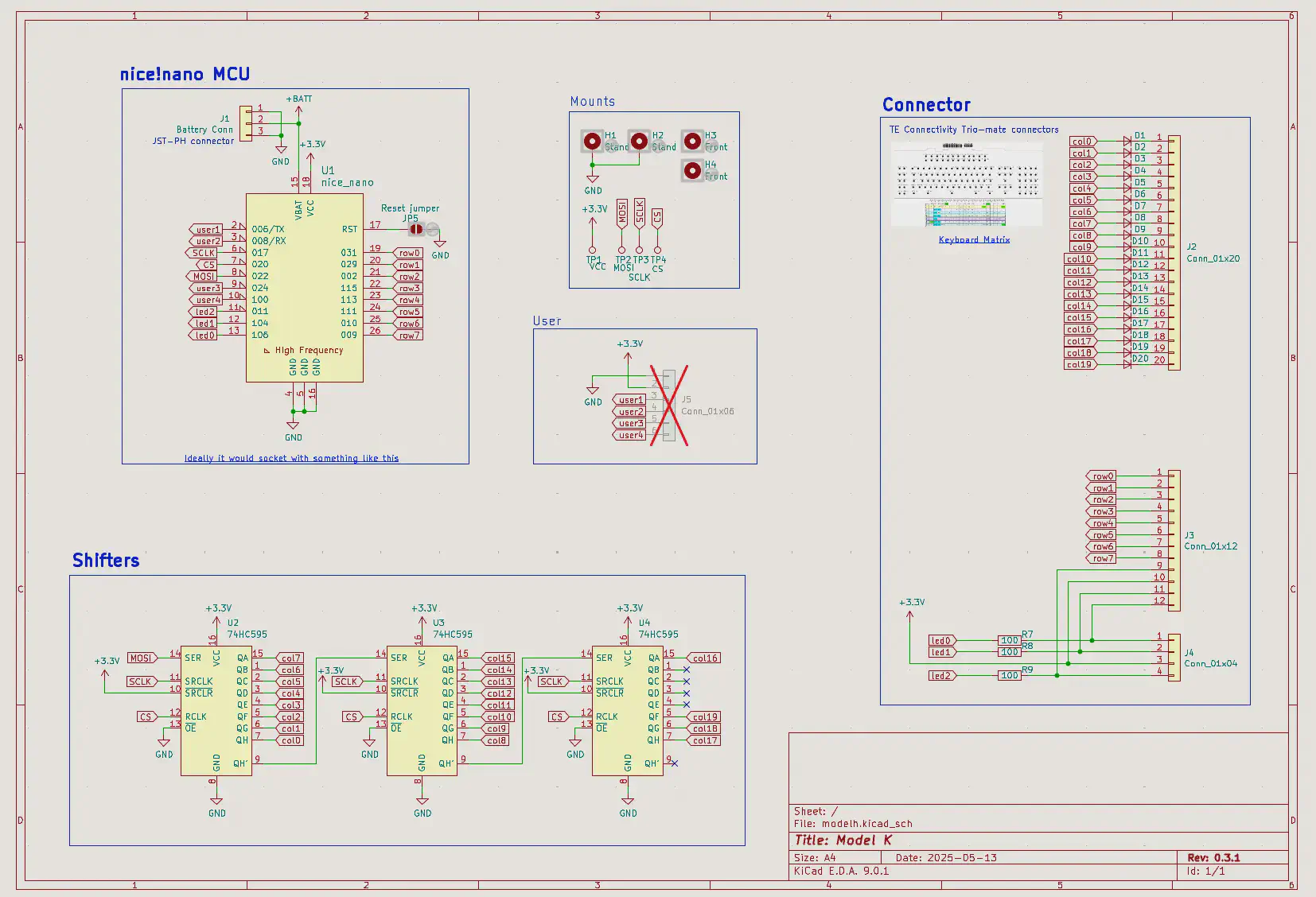

The schematic is simple, it’s just a wireless microcontroller (nice!nano in this case) and the same connectors the original board used. The nice!nano uses the nRF52840 chip, supports Bluetooth Low Energy, has a USB-C port and an integrated LiPo battery charger.

The microcontroller has fewer pins than the connectors, so it needs two shift registers2, which allows it to drive all 16 columns with just three pins. I had some pins to spare, I exposed a few as user pins, in case some of you freaks want to add a solenoid to make it even louder.

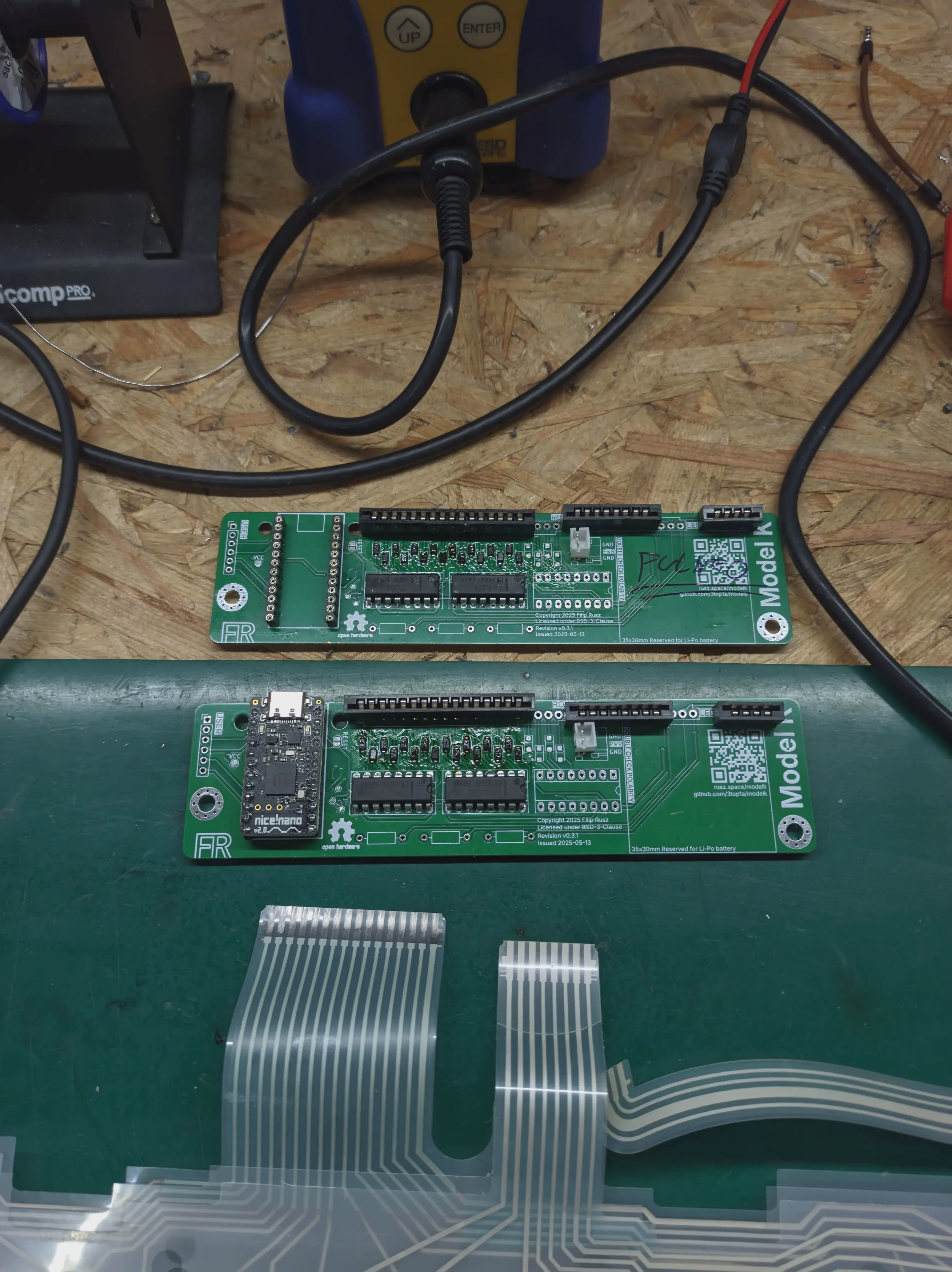

I got bored with redesigning it over and over again, so I ordered 10 PCBs on JLCPCB and waited a few weeks for the boards to arrive from China.

Looking back, the design had a few flaws. I wanted to reserve space for the battery and that meant the battery connection was a really long trace which is a big signal integrity no-no, and I used surface mount diodes to save on space which were a pain to solder.

But it turned out to be unusable anyways, because when making it, I moved the connectors a bit and that caused the microcontroller’s USB port to not align with the connector hole in the chassis.

But even then, it was acting very strange. Half of the keys didn’t register. I tried really cleaning the matrix contacts, checking the traces again and again, shorting the traces manually, everything. No matter what I tried, I just couldn’t fix it.. Long story short, turns out I soldered the connectors rotated by 180°, so half the connections didn’t make any contact.

However, after all that, it worked! After some lengthy programming, it typed like a normal keyboard!

I started daily driving it, which was possible despite the unreachable USB-C because it was wireless from day one. And it was perfect. Other than, you know, its flaws.

Actually Getting It Right

##It took me a month or so to design a new board3, but the new design improved everything – the connector is in the proper place, the battery connector is right next to the microcontroller, there’s a tab for grounding the metal backplate, and every component has proper spacing.

The soldering was a bit less painful thanks to the THT diodes, and I could reuse the microcontroller as it was socketed. I didn’t even have to reprogram it, it just worked once I plugged it in.

After taping a small 400mAh battery to the bottom case, and connecting everything up, I finally had a perfectly functioning wireless Model M. I haven’t tested the battery life on newer versions of the firmware, but when I did test it, it would last about three week.

TODO: Typing video, need to record

So yeah, that’s how I ended up with a keyboard about 14 years older than me – and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

-

Difficult is an understatement. I press the edge of the space key with my left thumb, but this was practically impossible, and I had to press the absolute center where the switch is. ↩︎

-

You can see three DIP sockets, I wanted to future-proof it so it would work on the 122 key Model M as well. Unfortunately during the last year I only found one on the market, and didn’t want to divert my very small disposable income towards another keyboard. ↩︎

-

And obviously a day after ordering it I made a better design that didn’t use any vias. ↩︎